From glowing caves to the frenzied flickering of flying night lights: bioluminescence is a phenomenon revered by many but understood by few. Our experts explain what’s behind nature’s stunning light display. And they tackle a burning question: could we harness living light sources for lamps?

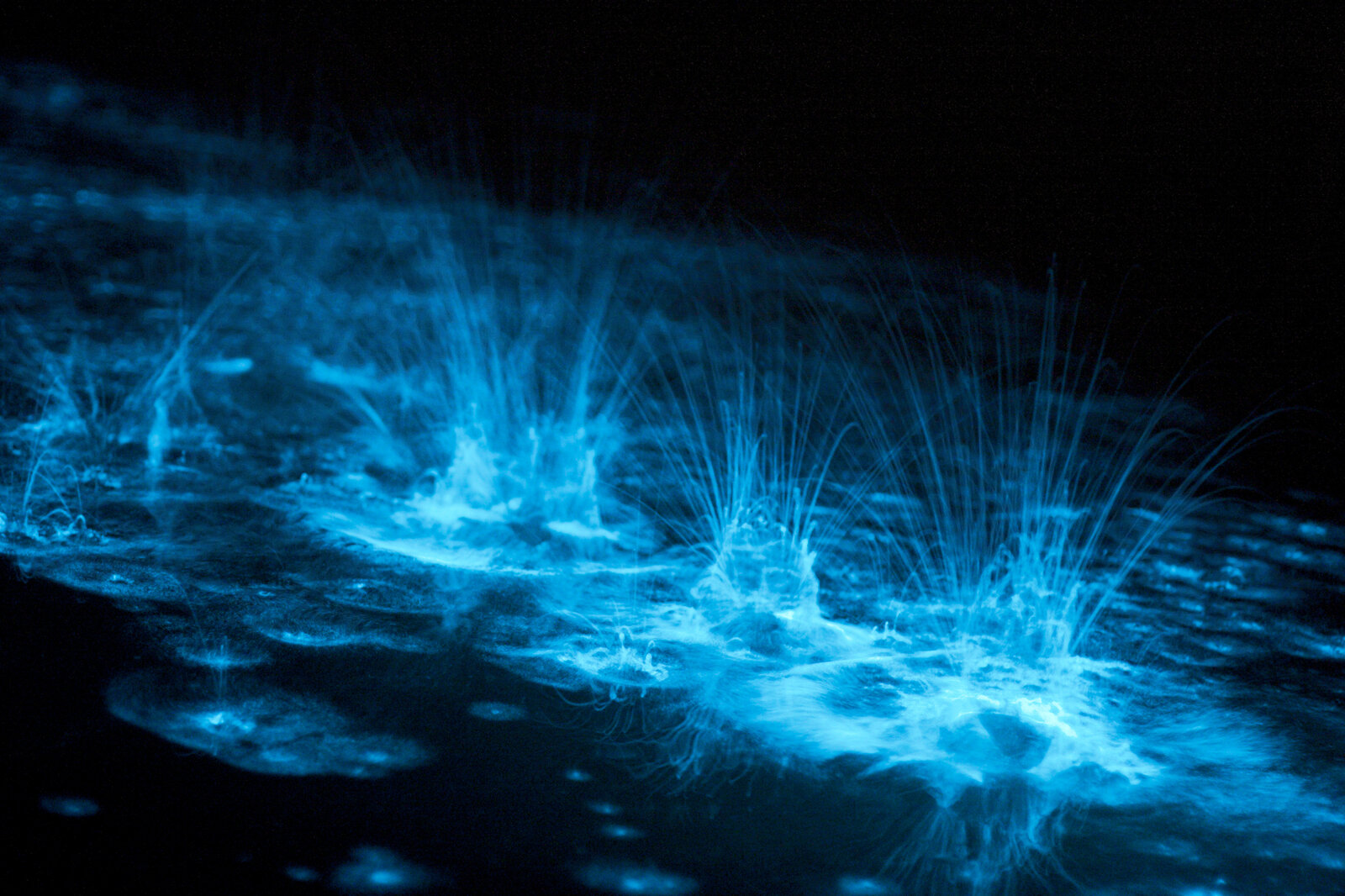

Falmouth, Jamaica. At first this world renowned lagoon’s black waters lie still. But then, with the slightest agitation, the water comes to life and a blue-green light glows from beneath. Folklore has it that taking a dip in these “Glistening Waters” is akin to showering in the fountain of youth. Women who embrace the ethereal experience are said to become more beautiful and look younger.

We know now that the glow comes from a high concentration of bioluminescent dinoflagellates – single celled organisms that emit light. But it is of no great surprise that throughout the ages, myth and legend has been attached to such other-worldly displays of natural beauty.

“The emission of light from fire, lightning bolts, stars or living beings attracts the attention of any human being. In the case of bioluminescence the light has a strange glow, something magic and mysterious,” says Cassius Stevani, Associate Professor at the Chemistry Institute of University of São Paulo and bioluminescence expert.

Bioluminescence is the emission of cold visible light by a living being. Perhaps the two best known cases of the phenomenon to the layperson are fireflies and glow-worms. Interestingly however, as Professor Stevani points out, these are neither flies nor worms: “Fireflies are actually beetles and glow-worms could be either the larval stage of flies and beetles or some adult beetles”. That’s us schooled.

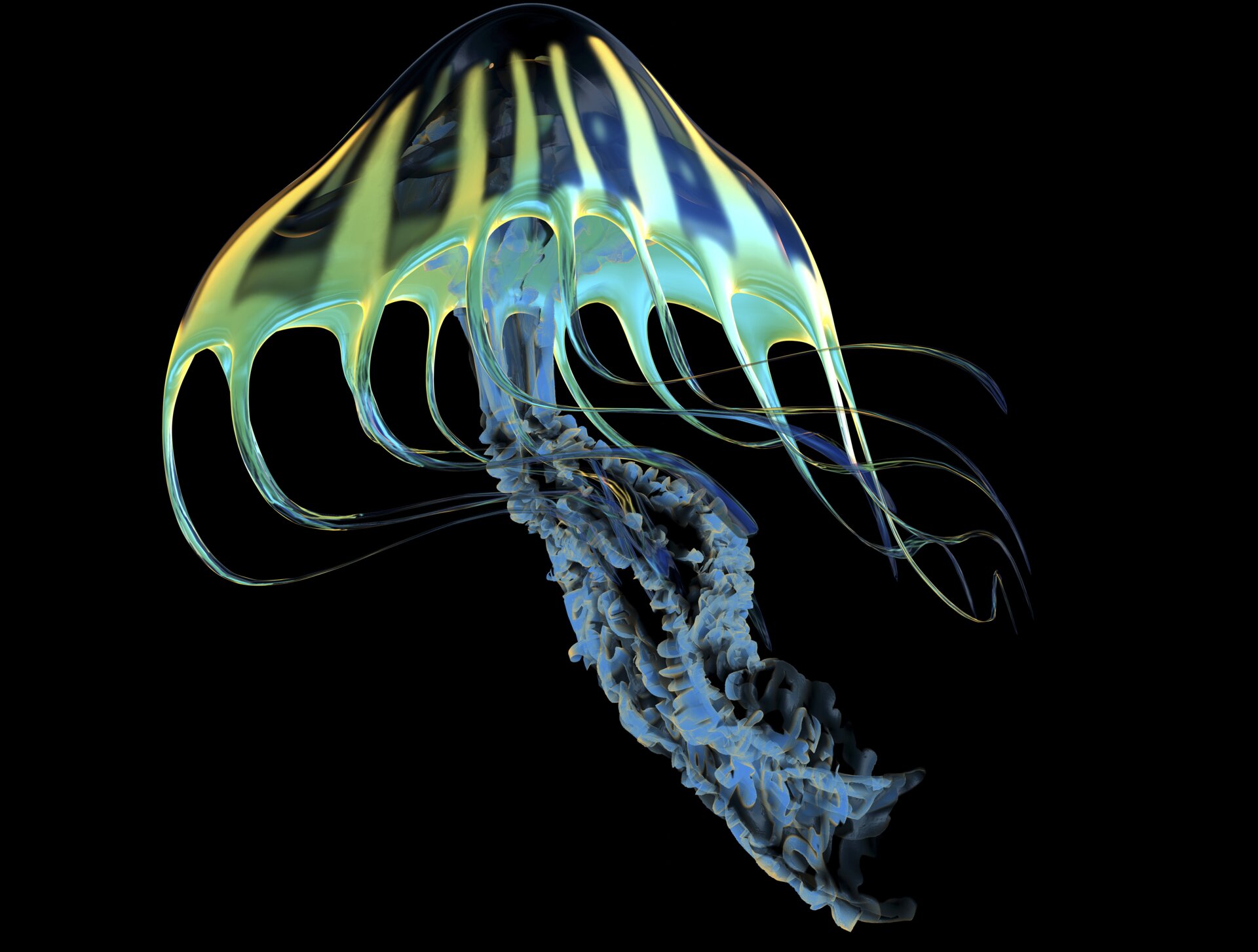

Bioluminescence is widespread among organisms on Earth but occurs most commonly in our oceans. “There are bioluminescent bacteria, dinoflagellates, fungi and animals such as insects, worms, jellyfish, crustaceans, mollusks and fish, but interestingly, there are no bioluminescent plants,” explains professor Stevani. As for the ocean dwellers, the emission of light might have conferred an evolutionary advantage to these deep-sea animals in a place without any additional source of light.

While the professor admits a slight soft spot for bioluminescent fungi – his primary research interest – it’s not just the glowing mushrooms that excite him: “Every organism has its own peculiarity and specific chemistry involved in the production of light. As a scientist, I’m keen to know how and why this process takes place.”

In general, the how is clear. Bioluminescence originates from a chemical reaction of a substrate, generically called luciferin, and an enzyme, luciferase. “It’s a kind of oxidation reaction like fire. However, fire is an uncontrolled chaotic process that releases energy as heat. Bioluminescence is a much more organized process, whose energy is released as photons which give you light,” says Professor Stevani.

As for the why, that depends on the organism – as Professor Stevani goes on to describe: “Fireflies use bioluminescence for communication, predation and sex courtship. Fish use it for predation, communication and as counter illumination. It’s likely that fungi emit light for the attraction of spore disperser agents.”

Obviously such light-emitting organisms are a far cry from their synthetic counterparts like LEDs – but they might be closer than you think.

“LEDs and bioluminescence actually belong to the same wide class of light emission process: luminescence,” Stevani explains. “The only difference is how the molecule or material is promoted to an excited state. Where electricity is used, it’s electroluminescence, where it’s a chemical reaction it’s chemiluminescence

– of which bioluminescence is one form.”

Another source of variety in the lamps we use is color. Again, you might be surprised that such variety exists in bioluminescence also: “You can have blue, red and green emission both in land and sea. It’s also possible to observe some mixing of colors yielding yellow and orange. Normally, blue is the color in the sea, but some jellyfish emit in the green region. Surprisingly, fireflies can emit in the whole visible spectrum.”

Let’s address the non-bioluminescent elephant in the room then: if such organisms as bacteria can produce light then can’t we just box them up and use them as a light source? Granted, that may be trivializing it slightly but is there a feasible commercial business opportunity for bioluminescence lighting our world?

Some start-up companies would certainly have you believe so – with claims of disrupting the way we produce and consume light, by offering a living and self-sufficient lighting raw material in the form of cultivated bioluminescent bacteria. Experts however, remain somewhat skeptical:

“They all think they have stumbled on to a novel and brilliant concept: free light!” claims Edie Widder, President, CEO & senior scientist at ORCA (Ocean Research & Conservation Association) in Florida and Bioluminescence specialist. “The trouble is, it’s only free until you calculate in the costs of production. Maintaining the narrow range of environmental variables required to keep the bacteria growing and glowing is energetically costly.”

As Dr Widder says, “Bioluminescence has many enormously valuable applications, but lighting the world isn’t one of them. LEDs powered by solar or wind energy make much more sense as a lighting solution.”

Professor Cassius Stevani is Associate Professor at the Chemistry Institute of University of São Paulo (USP) where he studies the mechanism of light emission in bioluminescent fungi. Find out more about him at:

Dr Edie Widder is a world renowned bioluminescence expert and deep-sea explorer who currently presides over the Ocean Research & Conservation Association (ORCA) in Florida.Find out more at the website: